Recent decades have seen significant improvements in the early detection of and treatment for some cancers.

The incidence of Cervical cancer has decreased in Australia since the introduction of a national screening program in 1991, and with the development of a vaccine that prevents infection with human papillomavirus.

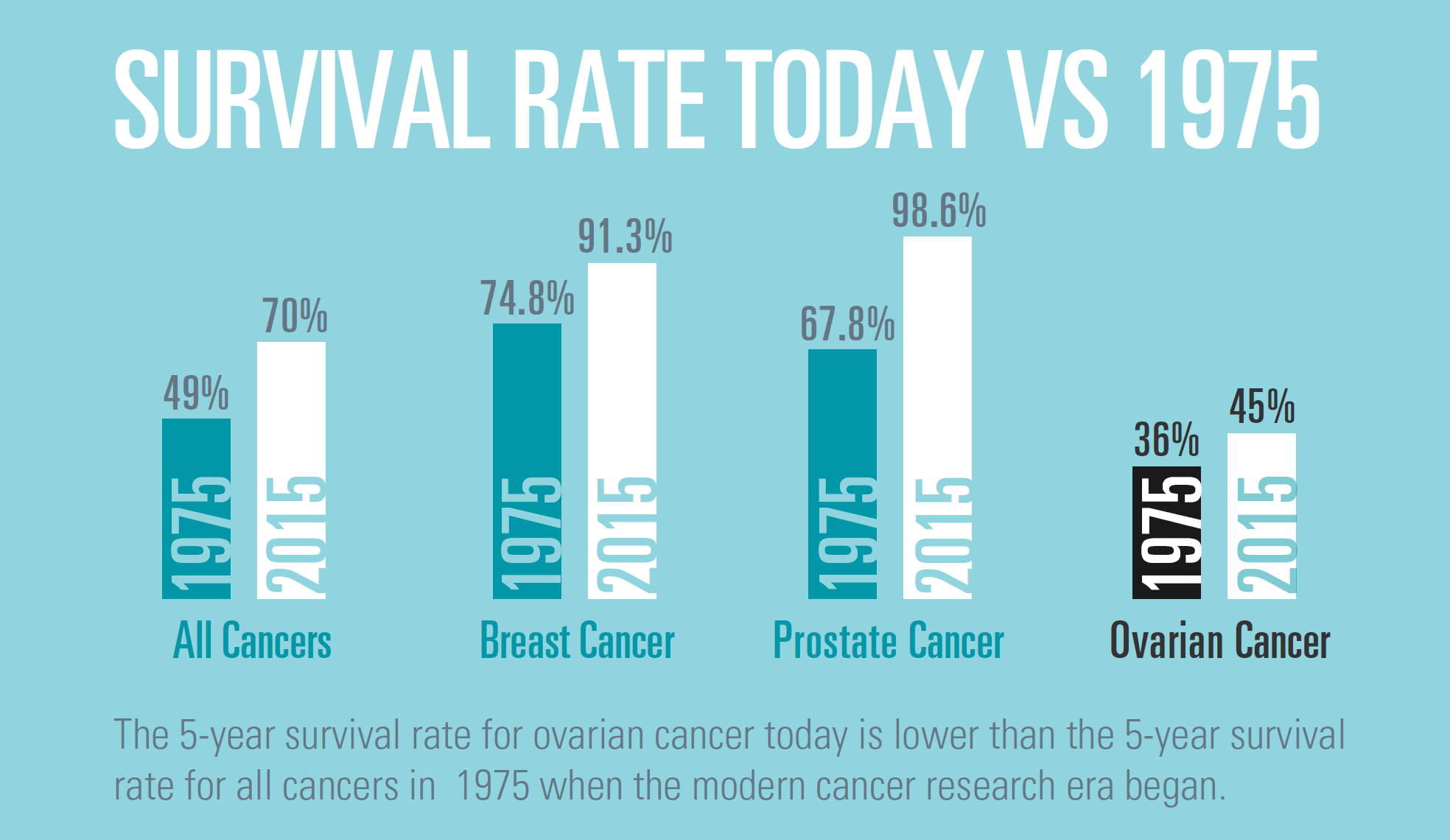

Similarly, advances have been made in both early diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer. The five-year survival rate for women diagnosed has improved from 74% in 1975 to 91% in 2015. The implementation of mammographic screening, and more recently, Breast MRI scans (particularly for at-risk women such as those with a BRCA 1/2 gene mutation), have contributed to improved survival by detection of disease at an earlier stage. Breast cancer treatments have also improved with the development of targeted medicines such as aromatase inhibitors, trastuzumab, and cyclin-dependent kinases 4 and 6 (CDK4/6 inhibitors).

These breakthroughs in other cancers show that it can be done. Yet the story hasn’t changed for ovarian cancers, for which decades have passed without significant progress in either diagnostic or treatment spheres.

Dr Geraldine Goss, a medical oncologist and member of the Ovarian Cancer Research Foundation’s (OCRF) Committee of Management, sees first-hand the urgent need for new treatment options.

“The chemotherapy combination that is currently used for ovarian cancer was published in 1996. Treatment options haven’t changed despite low survival rates.”

So, why is ovarian cancer so difficult to treat, and what are the challenges for researchers in the field?

Late diagnosis means delayed treatment

Associate Professor Stacey Edwards is a researcher at QIMR Berghofer who examines the role of genetics in ovarian cancers. Initially focused on breast cancer research, Associate Professor Edwards has been impressed with how far breast cancer treatment techniques have come, and so she has shifted her expertise to ovarian cancer research.

Associate Professor Edwards emphasises that ‘the cell of origin for ovarian cancers — where and how exactly the cancer arises and what cell type should be targeted — has proven difficult to determine and, in some research circles, is still being debated.’

Only in the last decade has it been discovered that frequently ovarian cancers originate in the fallopian tubes or peritoneal cavity, the space between the abdominal wall and internal organs — and from there it metastasises to the ovary. Since ovarian cancers are largely asymptomatic prior to metastasis, and because there is no early detection test, diagnosis often occurs at a late stage when it is most difficult to treat successfully.

.png)

The challenge of a one-size fits all approach

For most ovarian cancers there are three general factors that will impact the effectiveness of treatment:

- Whether the tumour is confined to the ovary/primary location or has spread

- Whether the cancer has been successfully treated but then has returned; or

- Whether the cancer has recurred despite being previously treated successfully and is now resistant to available treatment options, such as chemotherapy.

In addition to these general factors, tailored treatment options are required as there are many different types of ovarian cancers. The major subtype is high-grade serous carcinoma (70% of cases), while other subtypes include low-grade serous carcinoma (<5% incidence), clear cell carcinoma (10% incidence), endometrioid carcinoma (10% incidence) and mucinous carcinoma (<5% incidence). Most ovarian cancers are treated with surgery and chemotherapy, and sometimes additionally with drugs known as PARP inhibitors. These are currently the only available methods to treat ovarian cancers, yet up to 80% of women will experience recurrence. A broader range of treatment options may enable practitioners to treat the specific type of ovarian cancer more effectively.

New treatments require trialling – and trials require enough samples

For Dr Maree Bilandzic, a researcher at the Hudson Institute of Medical Research, developing more ovarian cancer treatment options is a priority. In her experience ‘getting enough samples to translate discoveries from the lab to treatments that could be used at the bedside is a major challenge.’

Before new methods of treatment can be used in general practice, researchers must first validate their method through trialling. When a research team is developing potential treatment options for a particular type of ovarian cancer, or to treat the disease at a specific stage, they must obtain enough samples of the specific type of ovarian cancer at the right stage for their project. Defined as a ‘rare cancer’, it can be more difficult to obtain samples for ovarian cancers than for other more common cancers in general, let alone the specific type of samples required for a particular research project. Additionally, given that ovarian cancers are asymptomatic, and there is no early detection test, late-diagnosis is common so finding samples at earlier stages of the disease to trial early-stage treatments is challenging.

The number of samples required depends on the project. For example, an early-stage clinical trial may require 10-20 samples. This might seem like a small number, however all samples need to be from patients who have had a similar treatment background, as different treatment backgrounds may skew the results of the treatment being trialled. Following an early-stage trial, sample numbers are required to increase exponentially as trial phases continue, from 10-100 for early stages through to several thousand often required for later-stage trials.

Taking treatment research from the lab to the bedside is expensive

Although the most lethal of the gynaecological diseases, ovarian cancers are considered rare cancers for which research has been historically underfunded. The State of the Nation in Ovarian Cancer: Research Audit, noted that approximately 1800 Australian women are diagnosed with ovarian cancers each year, compared with approximately 20,000 cases of breast cancer per year. Research funding covers the cost of laboratory equipment, processing of tumour samples, purchase of reagents and researcher salaries. When funding is prioritised towards a specific disease, advances can be dramatic, as illustrated by the lightning speed of development and trialling of COVID-19 vaccines. It can be done.

Where there’s hope there’s determination

Although expensive, the potential lives that could be saved are priceless. This is the attitude of the OCRF-funded researchers, who are currently working on promising projects including examining the role of leader cells in driving ovarian cancer resistance, and investigating new combination therapies, with the aim of inhibiting recurrence. With an ever-growing understanding of ovarian cancers and how they function, every dollar continues to contribute to future breakthroughs and more treatment options for women impacted by this terrible disease.

support australian researchers

Your donations enable researchers around Australia to apply for grant funding and work towards better treatment options for those diagnosed with ovarian cancer. Make a monthly gift to keep their research moving.

Donate monthly